Following the American Revolution, in the early part of the Nineteenth Century, pirates played havoc with trade along the Mississippi River from its headwaters to the Gulf of Mexico. Because the far western frontier of the new country lacked effective law enforcement, the areas around the Mississippi River and the Gulf were overrun by criminal activity.

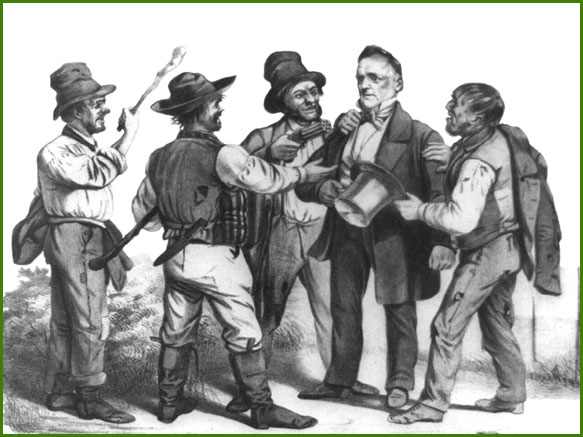

Brigands accost a well-heeled

gentleman in this Currier & Ives print

This was at the time that the new United States had just acquired the Louisiana Purchase, and the frontier was a mysterious, frightening, and huge place. In fact, it is thought that Meriwether Lewis, of the Lewis and Clarke Expedition, hired by Thomas Jefferson to explore beyond the Louisiana Purchase to find a water route to the Pacific Ocean, was murdered along the Trace long after his famed journey into the American Northwest.

One well-known pirate, Jean Lafitte of the Barataria Pirates [of southernern Louisiana], is reputed to have had a crew of one thousand. The mythology surrounding Lafitte portrays him as both criminal and hero. He considered himself not a pirate but a privateer. The black market provisions that he trafficked helped to maintain the Southern, and at that time far Western, reaches of the United States—an area neglected by most of the nation. New Orleans and the Delta depended on supplies from the piracy of Jean Lafitte. Reportedly, Lafitte did not attack American ships and took only from the Spanish and from other pirates.

Anonymous oil on canvas portrait, said to be of Jean Lafitte, early 19th century. Rosenberg Library, Galveston, Texas

The legend of Lafitte is romanticized and changeable. He was considered by some to be a gentleman and a savior to New Orleans, and by others a glorified thief and ruffian.

There are many reports of pirate activity here in the South. Pirates’ loot is said to have been buried near Ocean Springs by pirate Patrick Scott. The Pirate’s House near Bay Saint Louis might have hidden treasure because of underground tunnels which would have made the conveyance of treasure from the Gulf an easy operation. Kegs of gold are rumored to have been buried near Greenwood around 1865. The Copeland Gang, in the Bay Saint Louis area, are supposed to have buried treasure in Catahoula Swamp. A century before Lafitte, Pierre LeMoyne d’Iberville, with a crew of approximately thirty pirates, is connected with Ship Island (Isle de Vassiauz), a locale long recognized as a haunt for pirates preying on Spanish treasure fleets.”

Two sets of particularly evil, inhumane pirates plagued the river from Memphis to Natchez: the Harpe Brothers and Samuel Mason Gang, who were so bloodthirsty that they even repulsed other pirates.

Along the Mississippi River, just outside of Natchez, is a peculiar land formation called The Devil’s Punchbowl—very tempting to pirates. Harnett T. Kane in his book Natchez on the Mississippi, described the place:

“Far in the past, a great cup-shaped hole, about five hundred feet wide, had formed in the soft earth of the river bluffs. Slowly it seemed to widen, as gullies formed along its sides and rows of trees hurtled into its depths. Thickly grown, it provided a dim, almost impenetrable place of concealment. Natives thought a heavy meteor might once have plummeted here, sinking into the earth. Steamboat men claimed that their compasses behaved crazily when they passed.”

The Devil’s Punchbowl (right), looking out over the Mississippi River, is still an impenetrable and foreboding depression in the Loess bluffs just north of the city of Natchez. Standing on the edge of the precipice, staring into the gloom below, one can almost hear the raucous laughter of the Pirates of the Mississippi as they hurled the bodies of their victims into its depths. Photo by Bill Pitts

The Devil’s Punchbowl was a place for the hiding of treasure and the disposal of corpses. Mason’s crew would lure passing boats by posing as farmers with goods. Someone might cry out as if in trouble. Sometimes they would have a girl stand on the bank and call out as if in distress. Victims would be killed unceremoniously, stripped, and their bodies hurled into the Devil’s Punchbowl. The Masonites would throw in two bodies at once, betting which would hit bottom first. A terrifying time for travel and commerce along the Natchez Trace and the Mississippi River.

Whether the Mississippi River’s and the Gulf of Mexico’s pirates are romanticized characters or violent and despicable criminals, Mississippi’s coastlines saw periods of lawlessness that fascinate us. Though we are ethical and sympathetic beings, the ghosts of pirates stir the imagination. We look back on these terrible histories, and feel thankful to live in much more civilized times.

COPYRIGHT © 2010 THE NEW SOUTHERN VIEW EZINE | 2/21/12