This article first appeared in the September 2001 edition of "Mississippi History NOW," the website of the Mississippi Historical Society.

Excerpted with permission. You can read the entire article by clicking here.

World War II was truly a world war. All of the major countries and a large number of small nations were drawn into the fight. Even countries that tried to remain neutral found themselves in the conflict either by conquest or by being in the path of the campaigns of the major powers.

Not until November 1942, almost a year after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, did American forces enter the fight in North Africa. U.S. forces made amphibious landings and advanced from the west along the North African coast to Tunisia while British troops advanced from the east out of Egypt. The Germans and Italians had to defend on two fronts.

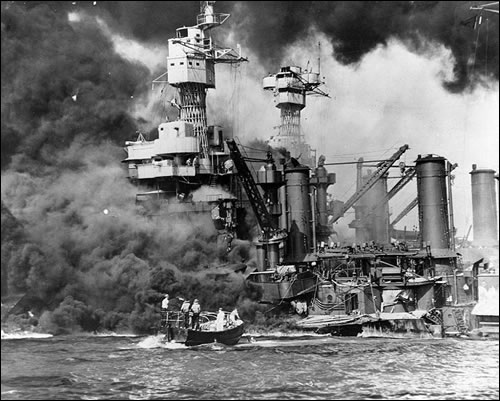

Pearl Harbor, Hawaii (left). A small boat rescues a seaman from the 31,800 ton USS West Virginia burning in the foreground. Smoke rolling out amidships shows where the most extensive damage occurred. Note the two men in the superstructure. The USS Tennessee is inboard.

Library of Congress

The famous “Afrika Korps,” under German General Erwin Rommel was besieged in Tunisia and fought on until May 1943. Two months later, the Afrika Korps became prisoners of war of the United States and Great Britain, 275,000 German and Italian soldiers. A decision was made by the U.S. government to bring the prisoners to the United States. It would be less burdensome and less costly to house and feed the captured men in the United States. Additionally, the prisoners of war (POWs) could be put to work in non-military jobs. In the last four months of 1943, German and Italian POWs began arriving in the United States from North Africa.

German prisoners await their turn to take off aboard a United States army transport plane at an advance air base in North Africa. Some of these were parachutists and tank corps men who fought with Rommel's Afrika Korps.

Library of Congress

Camp Clinton, one of four major POW base camps established in Mississippi, was unique among the other camps because [among its 3,400 POWs] it housed the highest ranking German officers. Twenty-five generals were housed there along with several colonels, majors, and captains. The high ranking generals had special housing. Lower ranking officers had to content themselves with small apartments. General Von Arnim, Rommel’s replacement, lived in a house and was furnished a car and driver. Some people swore that General Von Arnim attended movies in Jackson because the movie theater was the only air-conditioned place in town.

Hitler's refusal to allow Rommel to return to Tunisia in North Africa in 1942 led to the promotion of Lieutenant General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim (left) to full general and command of the Afrikan Corps. He was captured by the British Indian Army's 4th Infantry Division two months later.

Other major POW camps in Mississippi were established at Camp McCain [7,700 POWs] near Grenada, Camp Como [3,800] in the northern Delta, and Camp Shelby [5,300] near Hattiesburg. These base camps had most of the facilities and services that could be found in a small town — dentists, doctors, libraries, movies, educational facilities (English language was the most popular course) and athletics (soccer was the most popular sport).

POWs were guaranteed by an international treaty called the Geneva Conventions to get food, clothing, and medical care equal to that of their captors. POWs were housed in barracks that held up to fifty men. Each five barracks had a mess hall with cooks, waiters, silverware, and by all accounts very good food.

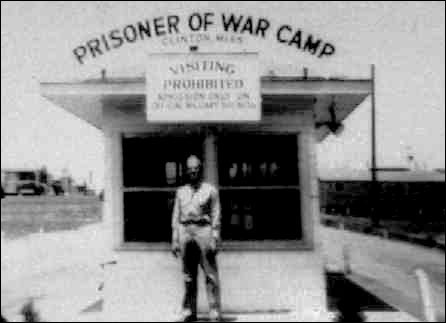

A view of Camp Clinton showing the office

on the left and several of the barracks on the right.

US Army Corps of Engineers

Under the Geneva Conventions, officers could not be forced to work. However, soldiers could be required to work if the tasks did not aid their captor’s war efforts. If the POWs worked outside the compound, they received a payment of 80 cents a day.

Perhaps the most intricate and useful work that was done by German POWs in Mississippi was the Mississippi River Basin Model. The U.S. Corps of Engineers was in charge of major waterways, and they had long wanted to build a one-square-mile model of the entire Mississippi River basin. Such a model could be of great value in predicting floods and in assessing the water flow of the Mississippi River and its tributaries.

Chief of the United States Corps of Engineers, Major General Eugene Reybold saw an opportunity to build the model. He would use German POWs from Camp Clinton to clear a one-square-mile area near Jackson. Using hundreds of wheelbarrows and shovels, the POWs prepared the site. They dug drainage ditches, they constructed miniature streets and bridges, and they formed the one-square-mile landscape into a miniature Mississippi River basin.

Eugene Reybold was distinguished as the World War II Chief of Engineers who directed the largest United States Army Corps of Engineers in the nation's history. German POWs (left) began work in August, 1943 on the Mississippi Basin Model using picks and shovels.

Captured soldiers often feel they have a duty to escape, but the possibilities of successful escapes were remote in Mississippi. Most POWs in the state were content to wait out the end of the war. Nonetheless, some POWs tried to escape. Escapees found it relatively easy to get out of the prison camps. They could walk off from a cotton field or slip off into the woods. They were hardly ever successful. Their German accents, their POW clothes, or their lack of money gave them away. Despite their failures, some POWs kept trying.

The main drive into Camp Clinton can still be seen on McRaven Road in west Jackson. Click here to see a current photograph.

At Camp Clinton the prisoners dug a tunnel 100 feet long. They hoped to tunnel under the fence. They concealed in their pants legs the dirt that they had dug out for the tunnel and then scattered the dirt around the prison grounds. They even installed light bulbs to light the tunnel. The tunnelers were caught 10 feet from the fence.

The war in Europe ended in May 1945, but the POWs remained in the compounds and continued to work — some for almost a year after the war ended. American soldiers were mustered out of the military quickly and efficiently, but President Harry Truman decided that a labor shortage existed in the United States and that the POWs should remain in this country until the labor shortage was over. Some POWs did not get home to Germany until mid-1946. They had been in the Mississippi camps almost three years.

Jubilant American soldier hugs motherly English woman and victory smiles light the faces of happy service men and civilians at Piccadilly Circus, London, celebrating Germany's unconditional surrender.

Photograph by Pfc. Melvin Weiss, England, May 7, 1945. National Archives

Over the years since 1946, German veterans have come back to Mississippi to see the camps that they lived in as young men. They are sad to learn that the camps were torn down after the war. The German POWs in Mississippi were probably aged 18 to 20 when they were captured in North Africa in 1943. The survivors of the Mississippi prisoner-of-war camps are now very old [Editor's note: this article was written in 2001.]. But many of those who are alive still come back to Mississippi to remember their experience. In a strange way the camps saved their lives. Unlike many other German soldiers who were killed in the war, these POWs survived. When they entered the Mississippi camps, their war was over.

John Ray Skates, Jr., Ph.D., emeritus professor of history, University of Southern Mississippi,

is the author of The Invasion of Japan: Alternative to the Bomb, published by the University of South Carolina Press, 1994.

COPYRIGHT © 2002 THE NEW SOUTHERN VIEW EZINE | 2/21/12