The Anole: Commonly known as the Green Chameleon

Enjoy Less-Threatening, Colorful Garden Reptiles

Garden snakes can certainly perform valuable services around outdoor plants, but finding a six-foot chicken or king snake when you are reaching for a weed can cause some people to have a coronary.

This female (left) boldly stares down the camera from her perch on a Mimosa trunk.

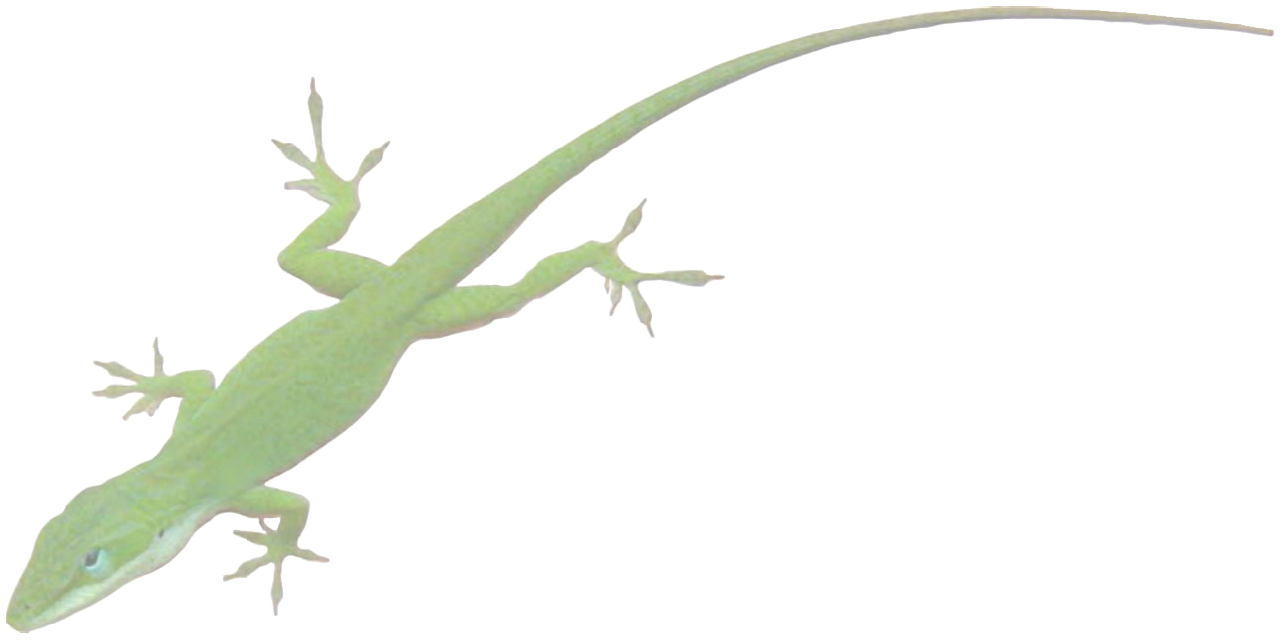

There is one reptile I do love having around the garden, and it is called the anole, pronounced “a-know’lee.” Like many of you, I grew up calling these green lizards chameleons. They probably got that name because of their ability to change colors. Like the chameleon, these 5 to 8 inch long lizards change colors as a method of camouflage from their enemies. They may change colors from green to brown, yellow or a mixture.

My first encounter with the anole was at the West Texas Fair in Abilene, Texas. I was six or so, and the anoles were for sale with a little collar and leash. You would pin the leash on your shirt or jacket, and let them roam around on your clothes.

A female anole (right, at top) encounters a male among some English Ivy. The male’s dewlap is barely visible in this photograph.

Today, I treasure these tropical lizards and have threatened to kill the family cat if I catch him with another in his mouth. The anole is known scientifically as anoles carolinensis and is native to the Caribbean as well as the Southeastern United States. An expert has told me that these colorful green lizards are being fruitful, multiplying and moving northward out of their range.

This has been my very best year for having babies born in and around my landscape. I would like to take credit for it, but I must admit anything I contributed was done pretty much as an accident. Whether it is my ferns, my wife’s airplane plants, the citrus trees or the salvia indigo spires, these little reptiles are there in baby, teenage and adult form. The anoles breed from March through October and lay one egg at a time. They bury eggs in loose, well-drained organic matter, humus or decaying leaves. They normally hatch in five to seven weeks, so it is possible to have several babies in a year.

This baby anole (left), perched on the photographer’s fingers, measures two and one-half inches from the tip of its snout to the end of its tail.

The male anole gives its version of a macho look by inflating or extending a large, pink fan of skin on its neck called a dewlap. You may have traveled the Caribbean and seen their iguana relatives do the same thing. This inflating of the dewlap is done to show his amorous feelings for some of the young ladies and to show his veracity to other males encroaching on his territory.

The thing we ought to all love about the anole is that they eat small insects, crickets, cockroaches, spiders, moths and grubs. Remember that service the next time you see one at home on the curtains in the dining room during a winter cold snap.

Anoles shed their skin in flakes (right), some quite large, which they consume while grooming.

If you have tried to catch them, you probably know one other defense mechanism. The tail is very fragile and drops off the body when grabbed, allowing it to escape predators. A new tail will grow that is usually shorter.

Anoles can be kept in a large aquarium having one male to three females. They will need water, gravel, misting, a bright light, a rock for basking, and green plants like ferns and philodendrons. They will need small amounts of live food and tiny bits of fruit like banana, oranges, and spinach. Leave the food for only 24 hours. They will eat approximately four live crickets a week.

Like butterflies and hummingbirds, the anoles bring a special pleasure to the world of gardening. Enjoy!